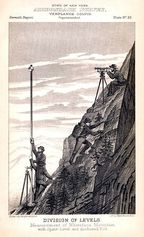

Plate from Verplank Colvin's Seventh Report to the New York State Legislature as Superintendent of the Adirondack Survey (1881).

Plate from Verplank Colvin's Seventh Report to the New York State Legislature as Superintendent of the Adirondack Survey (1881). Here is how he describes his journey up Mount Marcy, the highest peak in the Adirondacks and the source of the Hudson: "Down we plunged, down through the dense thickets of dwarfed balsam... Our rubber coats were speedily torn in ribbons, our clothing ripped and torn, and the icy drizzle of the clouds penetrated everything...Suddenly before us through the trees gleamed a sheet of water....It was a lake, and flowed...to the Hudson, the loftiest lake spring of our haughty river! First seen as we then saw it, dark and dripping with the moisture of the heavens, it seemed, in its minuteness and its prettiness, a veritable Tear-of-the-Clouds, the summit water as I named it."

Within a few years of his discovery, Verplanck was, like many other devotees of the Adirondacks, lamenting the opening up of the wilderness to the masses. And heaven-for-bid women outdoor enthusiasts. "The first romance is gone... The woods are thronged; hotels spring up as though by magic. The wild trails once jammed with logs are cut clear by the axe of guides, and ladies clamber to the summits of the once untrodden peaks."

While reading Colvin's written accounts of his surveys, and learning more about him, I see some similarities between William West Durant and this entrepreneurial explorer.

How do I dare compare the men? Well, consider both were exploring territory unfamiliar to them at the exact same time: William was plying the Nile River in Egypt while Verplanck was scaling Mount Marcy in 1869.

And they both passionately pursued their visions even when it did not end in financial gain. Verplanck at times, went unpaid by New York State. Yet he continued anyway, in extreme weather conditions, without adequate food or provisions, to reach the highest peaks.

And both men relied on the local native Adirondackers to make their dreams a reality. In fact, Colvin was dependent on the very guides he accuses of opening up the trails to the commoners, quite often employing Alvah Dunning, another famous Adirondack character that appears in my book, to blaze the trails for his expeditions up the mountainsides.

Likewise, William's camps would never have been achievable without the local craftsmen that knew the forests well enough to help him find timber and stone for building material.

According to their biographies, both men were also known to be task masters, expecting nothing but complete adherence to direction. However, in both cases these men take most of the credit for the work.

And both dared to continue their adventures in the Adirondacks in the most unforgiving seasons, a time when most other men might be tempted to hold off and continue until better conditions. Colvin surveyed the high peaks during snow storms in November, Durant scoped out the landscape for Camp Uncas and Sagamore during the winter months.

Sadly, both men died without achieving all of their intended plans. Although Covin can take credit for convincing the State legislature to pass an act creating the Adirondack Wilderness Preserve in 1885, he was ousted from his position as Superintendent in 1900 by then Governor Theodore Roosevelt. Because the state delayed or in some cases, refused to pay him, many of his maps stayed in his personal collection.

Durant's last big venture was also a failure. He couldn't find the backing he needed to continue construction on Eagle Nest Country Club, a resort that he hoped would deliver him from bankruptcy.

Here their stories dissever. Verplanck died at the age of 73 in a hospital for the mentally ill. William lived to age 83 and was fully in charge of his faculties.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed