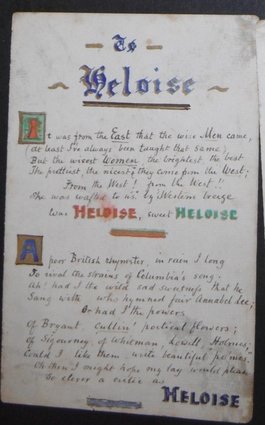

What a shock then, when, as I am editing the final draft of the last book in the Durant Family Saga trilogy: The Night is Done, I received an email from a person who holds Ella's scrapbook dated 1854-1920. It was given to them by one of Ella's distant relatives, Howard Rose, before he died in 1984, and saved from being inadvertently thrown out by his second wife. They had it kept it for 30 years and decided to do some research when they stumbled upon my website.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed